Out on Bail: Behind Alamance County's Bail Reform

Bail reform doesn't look the same state by state, and in North Carolina, there are holes as far down as the local level.

The agreement stated that those arrested in Alamance County will no longer be jailed because they are too poor to pay bail.

The agreement stated that those arrested in Alamance County will no longer be jailed because they are too poor to pay bail.

Intro: The Context

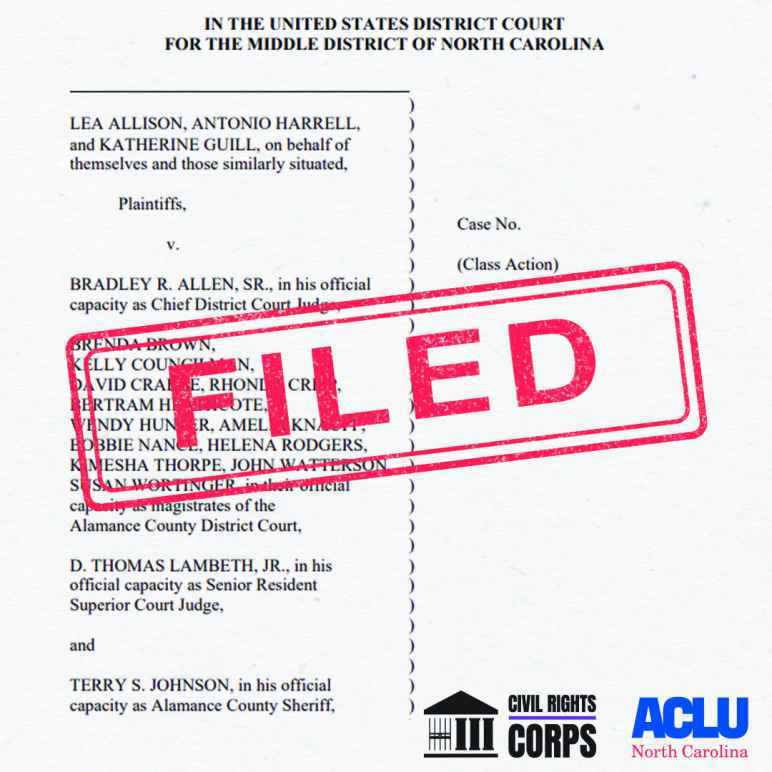

It has been almost a year since the American Civil Liberties Union and the Alamance County court system reached an agreement in the midst of the lawsuit filed by the ACLU. The lawsuit challenges local bail policy that put people too poor to afford bail behind bars.

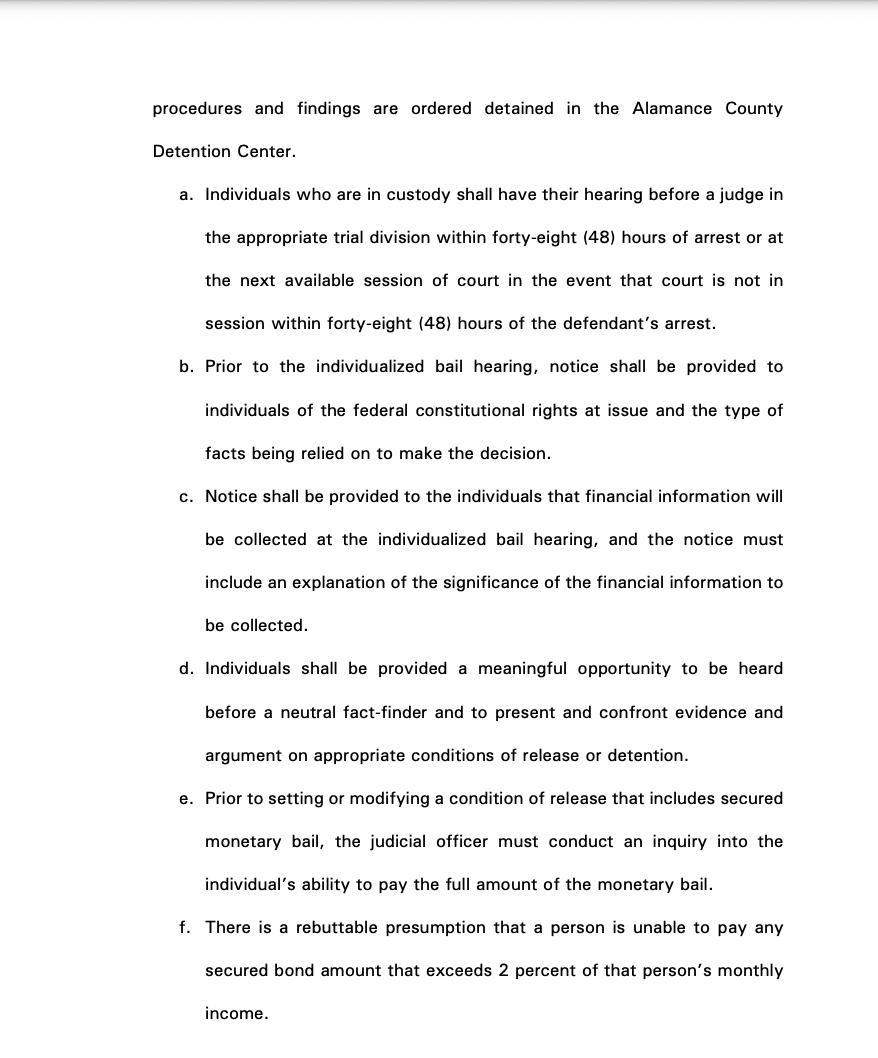

The agreement reached last May included court approved actions that ensure that a defendant’s ability to pay for bail is determined well before the bail amount is set. It also guarantees hearings with a judge at least 48 hours from the arrest and promises court provided counsel to assist the defendant during their first appearance in court when the bail amount is set.

The ACLU is still working on a class action suit that asserts that the Alamance County Courts violated inmate's 14th Amendment right to equal protection, pretrial liberty and due process. It also states that they violated 6th Amendment right to counsel. This project gives a glimpse at how bail practices in Alamance County have evolved over the years, how much they are the same and what to expect as the case moves forward.

Part 1: The History

Bail Laws have been integral to the the United States judicial system since the colonial period. However, it has long been a subject of debate amongst scholars and elected officials as cracks in the system have only increased with the evolvement of modern law.

For years, the bail process has been accused of being unfair, discriminatory and unjust to those who can not afford its steep price tag. In June of 1961, the Vera Institute of Justice decided to look more deeply into the process of bail in New York City. The groundbreaking Manhattan Bail Project of 1961 set the framework for studying inadequacies within national and local level bail.

The results of the study showed that individuals were more often released from custody without posting bail if they had strong ties to the community. The judicial court system labels this method as Release on Recognizance (ROR), which means that not only is the defendant released without posting bail, but it is done merely on the promise that the defendant will return. ROR is not a common practice used for most people in the community however, and was unavailable to individuals who lacked strong ties to the community.

The study not only set the framework for New York City, but changed how judicial courts nationwide approach ROR issuings. In 1964, Vera handed over their findings to the New York City Department of Probation. In the early 1970s, the city concluded that not enough effort was being placed on restructuring the pretrial services by the Department of Probation, and federal funding was issued by the city to Vera in an effort to work on the structure of pretrial arrangements.

The partnering of Vera and the city of New York made it possible for the city to correct inadequacies in pretrial arrangements. The federal funding enabled Vera to reassess the risk of defendant's failure to appear in court, establish a new ROR system, and completely cover criminal court arraignment across the city. The new program which still exists today is called the Pretrial Services Agency. The program shifted New York City’s criminal court system to a computerized platform, which served as a database that tracked all interviewed cases to their disposition in the criminal court.

The original computerized system was updated and financially backed in 1977. That same year, Vera renamed the program the Criminal Justice Agency (CJA), which serves as a non-profit backed by the city of New York. The program 44 years later is still assisting the city courts with release-bail decisions. The Manhattan Bail Project was one of the first studies ever released about improper pretrial arrangements, and called to question the legality of the corrupt nature of the system in place prior to the Manhattan Bail Project findings.

![[object Object]](./assets/vU1GOdF8In/screen-shot-2021-05-11-at-11-20-58-am-1040x990.png)

A clip from the original Manhattan Bail Project shows the finding that "a report to the court based on verified information improved the defendant's chances of release without bail."

A clip from the original Manhattan Bail Project shows the finding that "a report to the court based on verified information improved the defendant's chances of release without bail."

Part Two: How Bail Works In North Carolina

According to the Pretrial Justice Institute, "ninety-five percent of people in jail before trial in North Carolina are detained on secured bond (money bail)."

In 1984, the Bail Reform Act was passed and put into action nationwide.

Despite increased pressure on the judicial system to amend pretrial release, the Bail Reform Act enabled local court judges to make their own decision on whether or not an inmate faces pretrial release or detainment.

According to the 1984 Bail Reform Act, “pretrial release of the person on personal recognizance, or upon execution of an unsecured appearance bond in an amount specified by the court... unless the judicial officer determines that such release will not reasonably assure the appearance of the person as required or will endanger the safety of any other person or the community.”

This let judges on an individual basis decide the fate of inmates awaiting bond. The act creates a system in which inmates who can not pay the mandatory cash bond are subjected to harsher treatment in sentencing. Research shows that people who can not afford the price tag of a secured bail bond are more likely to receive an increased sentence.

The Bail Reform Act of 1984 enabled judges at the local level to assess whether or not an inmate is a threat to the community, and states like North Carolina prove that cash bonds are issued inconsistently from county to county.

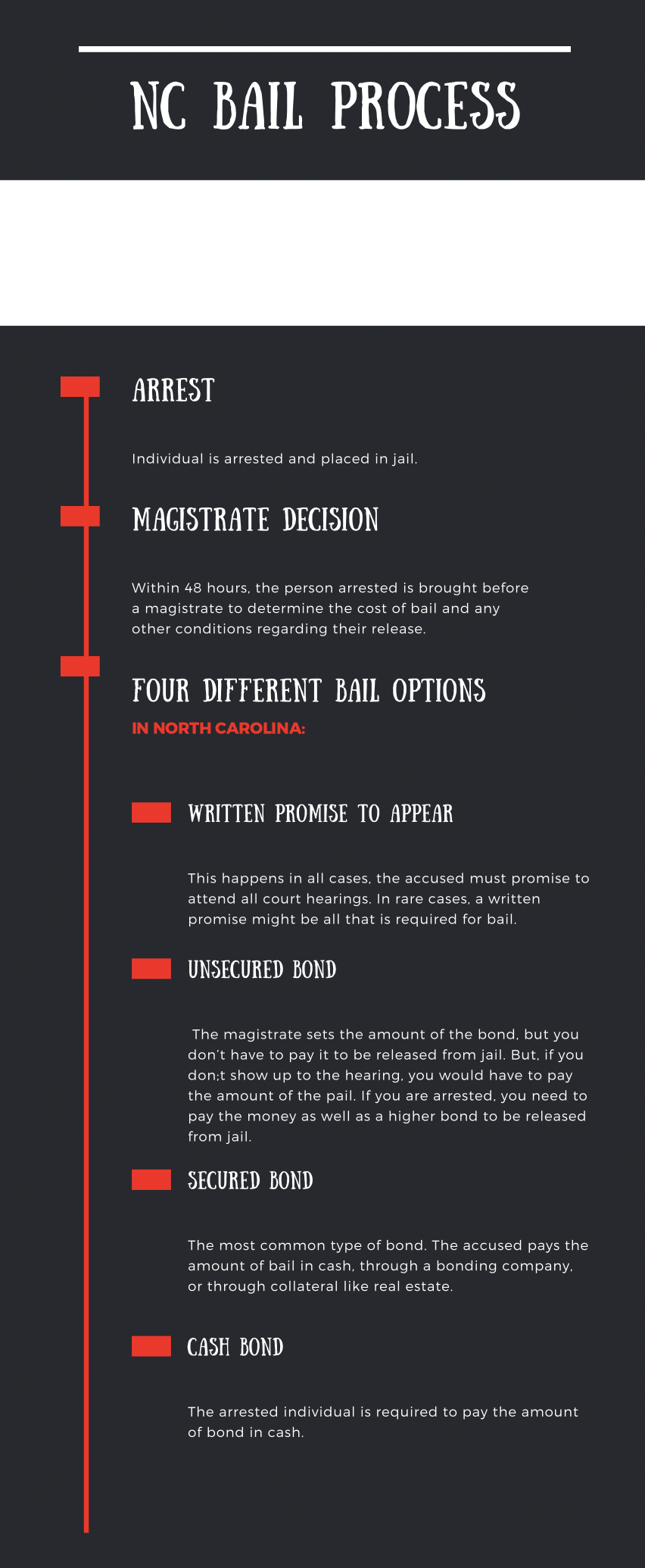

While the four different types of bail are used in North Carolina (see figure 1), the most common is the secure bond. After the enactment of the 1984 Bail Reform Act, the deciding power for the type of bail became subjective to local officials on a court by court basis. As shown in the Pretrial Justice Institute Study, North Carolina officials have consistently resorted to claiming a threat to public safety in order to detain the arrested individual.

The study states that:“Even though North Carolina statutes establish a preference for non-monetary pretrial release, “ninety-five percent of people in jail before trial in North Carolina are detained on secured bond [money bail].”[3] This means ninety-five percent of people accused of a crime are being detained in prison before they have been found guilty.”

This has shown to create inconsistencies on a county to county basis throughout North Carolina. Specifically, “it seems that regardless of the law, local judicial officials can find ways to implement cash bail.”

Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Part Three: What Bail looks like in Alamance County

Kristen Powers, of the Alamance County Bail Fund, shares insight on an example of the cracks in Alamance County's bail system.

In the scope of bail issues and practices, Alamance County is one of North Carolina’s shining stars, in the sense that it has been targeted by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) bail reform lawsuit.

What are the biggest bail issues currently plaguing the Alamance County prison system?

Kristen Powers, a member of the Alamance County Bail Fund, discussed some of the main problems in Alamance County’s bail system. Powers said that the bail amounts in Alamance County are being set “disproportionately high” -- so high, that Powers said that most people in Alamance County could not afford the set bail amounts.

Listen to Powers discuss the complexities of bail reform in Alamance County.

“We’re not seeing in Alamance County, or really across the state, this consideration of the ability to pay,” Powers said.

This lack of consideration has led to poor people ending up stuck in jail simply because of their finances, according to the Alamance County Bail Fund’s website.

According to Down Home NC, a collective that hosts the Alamance County Bail Fund, Alamance County’s current bail system is about 25 years old.

The website also asserts that poor and working people are at a disadvantage in the bail system because they are not being provided attorneys to represent them when bail is actually being set.

Powers also discussed the role of bail bondsmen in the Alamance County bail system. She said that, since most people cannot afford their bail, they have to rely on a bail bondsman who earns a 10 to 13 percent profit from paying out bail.

The one caveat to being a bail bondsmen, according to Powers, is that they will refuse to touch bail in circumstances when they are not able to make a large profit. This caveat came into action during one of the times Power first helped bail someone out as a member of the bail fund.

A Bailout Anecdote:

The individual, one of the fund’s first bailouts, was being held in Alamance County Detention Center for a bail of $350.

“But nobody in his family had $350,” Powers said. “The amount was so small that the bail bondsmen do not touch it, because it is not worth their time and energy to basically get $30 for their effort.”

The individual ended up staying in jail for several weeks without any sort of conviction securing his lengthy sentence.

“If we had not intervened,” Powers said. “His court date was not for several more months, so he would have stayed incarcerated in the jail.”

Powers continued, saying that the individual still would have served that time even if he was found not guilty because he did not have the money.

“That was the only reason that he was there,” Powers said.

Alamance County Prison System and Transportation

When asked about what types of crimes people face disproportionately high bail for, Powers referred to trespassing, and said that people were placed in Alamance County Detention Center for petty crimes like these before they were brought to trial.

“So people are sometimes being held in detention centers to protect community safety for things they have not even been convicted of,” Powers said. “There’s no connection necessarily to whether they did it or not.”

Listen to Powers' full explanation here.

The third and final issue that Powers cited in the Alamance County bail system is the issue of transportation to courts in a rural community. Since there are no public transportation systems in Alamance County, getting to various locations without a car can be difficult. This problem is amplified for those who cannot afford either bail or a car.

“That makes it hard to show up for your court date,” Powers said. “Especially when court sometimes starts at 9 a.m.”

The Lawsuit

On November 12, 2019, the bail issues in Alamance County reached a boiling point.

The ACLU, on behalf of multiple plaintiffs, filed a class action complaint against multiple people in power in Alamance County. Among the defendants were the Senior Resident Superior Court Judge, the Chief District Court Judge, all county magistrates and the Sheriff, according to the University of North Carolina School of Government blog on North Carolina criminal law.

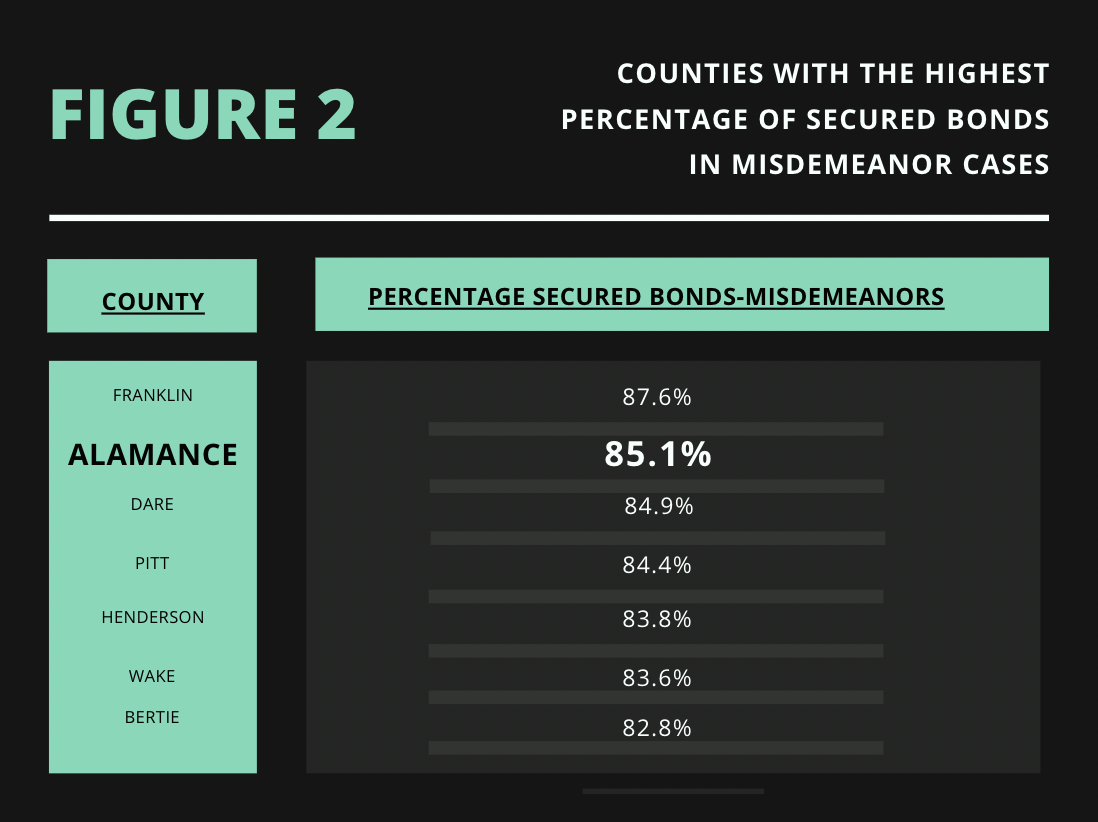

As shown in figure 2, Alamance County has the second highest rate of counties in North Carolina for percentage of secured bonds-misdemeanors.

As shown in figure 2, Alamance County has the second highest rate of counties in North Carolina for percentage of secured bonds-misdemeanors.

AP Photo Kira Silbergeld.

AP Photo Kira Silbergeld.

Alamance County Jail. AP Photo Kieran Ungemach.

Alamance County Jail. AP Photo Kieran Ungemach.

Alamance County Jail. AP Photo Kira Silbergeld.

Alamance County Jail. AP Photo Kira Silbergeld.

The North Carolina Criminal Law Blog is shown here, on the Alamance County Bail Litigation.

The North Carolina Criminal Law Blog is shown here, on the Alamance County Bail Litigation.

Part Four: What's Next?

While the agreement made last May has made significant headway for people in Alamance County charged with crimes who cannot afford bail, the battle in the courts still continues with the civil suits of three Alamance County residents.

The plaintiffs were all put behind bars pretrial because they could not afford bail, and two of them were not provided with counsel at their magistrate hearing when the bail amount was set.

The Alamance County Courts have yet to confirm nor deny any of the allegations brought against them in the suit, like violating the plaintiffs 14th and sixth amendment rights.

Staff attorney Leah Kang with ACLU North Carolina described the current status of the case that was filed all the way back in 2019, and the implications of the consent preliminary injunction filed last year.

“We are still in the process of monitoring how that policy is being implemented,” Kang said. “The local officials who are in charge of the pretrial release policy are still in the process of meeting and discussing implementation of the consent preliminary injunction.“

She also noted that new reform places the bail bond industry, which holds a large presence in Alamance and other counties across North Carolina, in the spotlight as to what they really offer their communities.

“The idea that the bail the bail bond industry appears to provide provide money for bail when we know bail doesn't work, I think it's time to rethink that industry altogether, just as it is time to rethink the practices of setting bail altogether,” Kang said. “It is, at the end of the day, an industry that profits off of a system that criminalizes poverty.”

Kang has been working on the ACLU case since it was filed, and noted that while a timeline for the conclusion of the lawsuit is unclear, and the consent preliminary injunction is great progress, more needs to be done.

“This is a substantial step forward, particularly considering where Alamance County was, and the practices it was engaging in,” Kang said. “Policies need to be implemented in a way that ensures that people are only being deprived of their fundamental right to pretrial liberty where it is absolutely necessary, and there are no there are no other alternatives.”

Some of that work is what Powers is also hoping to accomplish in the near future with Down Home, as other counties are experimenting with reformed bail practices.

“We've seen counties like Haywood & Jackson that are experimenting with different types of pretrial systems that really analyze who is getting bail and how much bail is being set,” Powers said. “There is also legislation being introduced that addresses eliminating bail for misdemeanors.”

While many of these legislations remain unmoving in committee study according to Powers, the fact that they are still being introduced is progress in shifting people’s mindsets toward bail reform.

“The presence of these bills is also an indicator that people are interested as constituents and seeing a world where people are not incarcerated for not having money,” Powers said. “That is some of the cultural shifts that we are seeing across the state to push people to really consider what could be an alternative to bail.”

For Kang, this case is not the end, and she hopes the push for bail reform continues around the state, and with

“For North Carolina, statewide and still in Alamance County, no one in the public should rest until the use of bail as a way to punish people for their poverty is ended,” Kang said. “It is such a stain on our commitment as a country and as a state to equal protection under a just system of laws.”

![[object Object]](./assets/ZRDCGlxRw2/screen-shot-2021-05-10-at-4-37-16-pm-844x846.png)

![[object Object]](./assets/nRdVLh4yK7/screen-shot-2021-05-11-at-11-30-51-am-1960x1054.png)